Managing Uncertainty to Maximise Project Value

Following the recent Value Management Into the Future conference, we look back at an insight into how managing uncertainty can maximise project value.

This paper considers the subject of uncertainty in both of its manifestations as a positive source of opportunity for value maximisation and a degrader of the value potential of new ideas. As an overall introduction to different ideas on uncertainty and its management, the paper takes account of the interesting viewpoints of a selected number of researchers and writers. From their insights into uncertainty and ideas on how to manage particularly strategic issues to do with uncertainty, this paper proceeds to delineate those areas felt to be of use to practitioners in the field of value management. It will also propose areas where they may augment and strengthen a value engineering work plan and thereby increase value for a project.

A Definition of Uncertainty

Uncertainty is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘not certain, not to be depended upon, changeable’ and it is fair to say that in most peoples minds uncertainty is inextricably intertwined with ideas concerning risk. This association is one reason that uncertainty tends to be used in a pejorative sense when it is discussed on a project. Negative concepts abound concerning risk and it is generally considered as something that is, if possible, to be avoided through the correct application of risk management. However, ideas on risk and uncertainty are changing and it is now recognised for risk that there is an obverse aspect that is fertile ground for project enhancement. These starkly contrasting aspects have also interestingly started to be picked up by national organisations responsible for risk or project management. The UK Association of Project Management (APM) thus has moved to a definition of risk as follows:

A combination of the probability or frequency of occurrence of a defined threat or opportunity and the magnitude of the consequences of the occurrence.

The US Project Management Institute (PMI) has a similarly double-edged definition of risk contained in their publication Project Management Book of Knowledge, where risk is defined as:

An uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on a project objective.

Although risk and uncertainty have similar fuzziness and unpredictability, some of the referenced authors have attempted to distinguish some fundamental points of departure. Achrol (1988) attempted to differentiate between them as follows:

Risk is said to exist in situations where each outcome has a known probability of occurrence, whereas uncertainty arises where the probability of the outcome of events is unknown.

Other authors have associated uncertainty with a shortage of information. Galbraith (1977) is cited by Kolltveit et al in the following quotation:

Uncertainty is often defined as a result of a shortage of information, defined as the difference between the amounts of information required to perform the task and the amount of information already possessed by the organisation.

Hence, as a proposition,it is suggested that uncertainty has characteristics that define it and take it beyond its sibling risk; these include an inability to be reduced by probability prediction and a lack of information that makes it impervious to further attack by linear management approaches. Paradoxically, this fuzzy opaqueness also ensures it possesses useful twin aspects. Whilst being concerned about the negative erosive aspect a Value Manager can take advantage of its positive aspect to deliver ideas out of a creative session that have the power to enhance project value considerably.

It will also be proposed in this paper that by deliberately looking for and examining uncertainty within a Value Management workshop, a further viewpoint is provided that can add another dimension of insight, questioning and revelation. This can inspire new ideas for increased value and later in a workshop warn a team of further areas to consider ahead of promised benefits being eroded by unforeseen effects of the negative aspect of uncertainty.

Concepts of Uncertainty

The wider interest in uncertainty has grown in parallel with, but lagging, that of risk. As that been stated, uncertainty is often viewed as the dark force pervading the universe of risk. The growth in understanding and research of risk has allowed a wider definition of risk to be accepted that acknowledges a dynamic dichotomy that takes in a probable threat and a possible opportunity. As the enquiry into risk has broadened so the faint outline of uncertainty has come into view, that in an apophatic sense enables us at the least to know what uncertainty is not, and this knowledge allows a strategy for management to be evolved.

This article fully acknowledges the contribution and insights of the referenced authors and some of the important points of selected papers and books are recapitulated here in order to set out the basis of agglomerating certain key activities and developing a new approach to uncertainty management that is aligned with the especial requirements of a value management workshop.

Demarcating Uncertainty

Kolltveit et al (2004)describe an up to date view of both risk and uncertainty that embraces the twin aspects of threat and opportunity and in making the case for the latter include several illuminating real life examples of how a situation of gross uncertainty can with judicious management and good timing turn an impossible or unattractive proposition into a highly profitable conclusion.

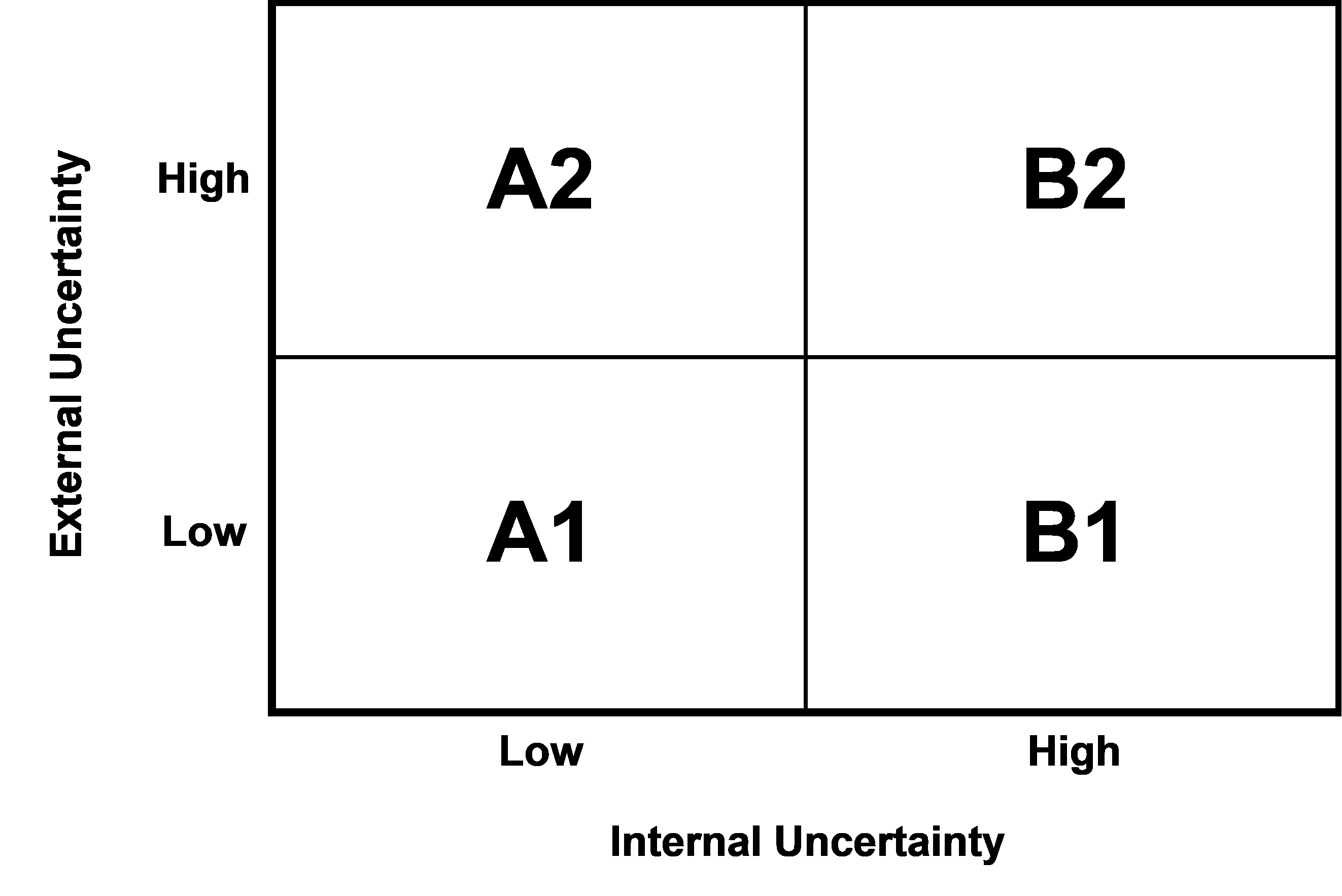

In attempting a strategy of uncertainty management a case is made for the division of uncertainty into external and internal forms..

External Uncertainty

External Uncertainty is defined as a ‘shortage of information related to the external factors that may affect project performance’. The factors that are considered to be grouped within this external category for a significant project include:

| External Factors | |

|---|---|

| External Uncertainty | |

| Political situation | |

| Contract | |

| Local infrastructure | |

| Cultural situation | |

| Currency stability |

Table 1: External Uncertainty and Sources

[Source: Developed from Kolltveit et al 2004]

Dependent upon the project and the industry, many more factors can be added to this list, such as environmental, social, safety and competition, etc. The essential point is to firstly identify, then to locate uncertainty sources as either external to the project or internal to it.

Internal Uncertainty

Internal uncertainty is defined by Kolltveit et al as ‘lack of information related to a project’s internal factors that may affect the project performance’ . As with external uncertainty, there is an attempt to group and classify sources of internal uncertainty as follows:

| Internal Factors | Issues | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Uncertainty | ||

| Technical concept | Technical quality of concept Fit of preferred option with overall business Fit of preferred option with external environment | |

| Goals | How realistic? Too ambitious? How many and are they conflicting? | |

| Team | Project management competence Capacity or resources Adequacy of organisational structure |

Table 2: Internal Uncertainty and Sources

[Source: Developed from Kolltveit et al 2004]

Once again, many more potential sources of internal uncertainty can be postulated but the items in Table 2 have a commonality built from the project team and its internal workings and approach to tackling the external demand of delivering a tangible project.

Uncertainty Affecting Decisions

The pioneering work on practical management of uncertainty through time on major planning problems that is described in Friend & Hickling Planning under Pressure is now in its third edition and the methodology known as the Strategic Choice Approach has been disseminated around the globe. What this book describes is the culmination of research, study, verification and refinement on how people with responsibility for making decisions in real life respond to the multi-faceted challenge by invoking responses to uncertainty arising from the technical environment, wider related political agendas and guiding values considered to influence the decision. The formulation and use of this knowledge into an overall methodology constitutes the Strategic Choice Approach. Although the method is designed to assist principally in matters concerning planning, policy and time bound decision-making; the interest to this paper is the identification and management of uncertainty as the central and critical components of dynamically making better value decisions.

The Strategic Choice Approach grew out of a pioneering research project undertaken by social and operational research scientists from the UK Tavistock Institute for Human Relations in the 1960’s. The four-year research project based in the major city of Coventry was concerned with examining how in practice politicians, administrators, planners and professional experts inter-acted and worked together to evolve solutions to real life problems. The problems included a review of a development plan, urban road network redesign, school system reorganisation, public transport finance, housing stock renewal and capital works scheduling. The observations and results from the research were distilled into a new empirical methodology that incorporated the practice of how people reacted to the influences of uncertainty but grafted onto this a strategic way of guiding them to progress to decisions, notwithstanding the uncertainty. The original research noted that persons involved in decision making in complex circumstances encountered repetitive dilemmas that included:

- Problem issues and the concept or understanding of the problem being faced tended to change and mutate with time

- Action was required even when there was a desire to hold off and take a broader view

- Decisions were pulled in opposite directions by urgency and uncertainty

- Political and technical aspects of the decision became blurred and undifferentiated

It was observed that decision makers when confronted with a need to make a decision and experiencing difficulty due to uncertainty would tend to respond in one of three ways:

- By exploring technical responses to the problem through, for example, examining costs, forecasts, technical analysis, further research or refinement of mathematical or financial models. This type of response could be summarised as exploring responses to the decision makers environment.

- By exploring policy values that should guide actions such as, for example, formal or informal activities to clarify goals, objectives, aims or policy guidelines by talking to anyone from policy authorities to a wider involvement of stakeholders currently under-represented in the decision. This type of response could be summarised as exploring responses to the decision makers values.

- By exploring a wider perspective of the decision since it might be argued that the problem is caused by a partial view of a larger whole that has additional decision problems attached. This exploration may consist of planning, co-ordination or negotiation that permits the current decision problem to be examined in conjunction with other possibly linked issues. This type of response could be summarised as the decision maker exploring responses to decisions that are related.

Thus, by observation, it was noted that the uncertainty affecting the decision making process could be ascribed to three principal sources:

| Identifier | Uncertainty Type | Decision Makers Typical Responses |

|---|---|---|

| UE | Uncertainties about the working environment | Acquire more information |

| UV | Uncertainties about guiding values | Clarify objectives |

| UR | Uncertainties about related decisions | Enlarge decision making view |

Table 3: Uncertainties Identified in the Strategic Choice Approach and Typical Responses

Dealing with an Uncertain Future

The discussion of research and development projects that exhibit high uncertainty in the article by Courtney and Lovallo describes the situation where the normal tools of prediction cannot be applied for projects that have high uncertainty. Whilst some contrition is required to accept that an unpredictable future is sometimes just that – unpredictable, the authors point out some approaches concerning the management of uncertainty that have merit.

It is argued that the boundaries of uncertainty for a project need to be tested first by the use of all the normal tools of investigation that a project manager may have at his disposal, so that the outline of a hard residual uncertainty is revealed by subtraction from those elements that can be discerned through the investigation.

The resulting residual uncertainty can then be assessed to see which of four categories it is believed to lie within. Knowing which category the uncertainty lies in will then determine the suggested approach to calculate a predicted return on investment. The categories for residual uncertainty are:

- Level 1 Uncertainty: where the uncertainty is negligible and normal methods of return on investment analysis are adequate;

- Level 2 Uncertainty: where uncertainty is more marked but investment analysis can identify a limited set of discrete returns on investment;

- Level 3 Uncertainty: the effect of uncertainty is more pervasive and only permits a range of possible returns on investment to be projected;

- Level 4 Uncertainty: no normal method can predict even a range of possible returns in investment due to the pronounced uncertainty and resulting ambiguity of outcomes. This situation involves an encounter with ‘true’ uncertainty.

The treatment of the first 3 forms of uncertainty (which are not true uncertainty) involve the use of traditional forecasting techniques, that become increasingly sophisticated as the degree of uncertainty rises with each step up in level. The level 4 uncertainty will not yield to any such frontal assault, however sophisticated the software or method. To manage level 4 uncertainty, the authors argue that a reversal of the viewpoint from trying to anticipate the future (as for level 1-3 uncertainty) needs to change. The recommended approach would take a postulated future and works back to the present whilst asking ‘what would I have to believe?’ at each of the intervening development stages prior to reaching the desired project end. Such questioning introduces a rigour to the management of a highly uncertain project and requires the project team to make manifest the assumptions underpinning the usually optimistic end prediction for the uncertain project. It also requires the project team to construct a number of milestones that the project development can thereafter be measured against. The checking of such milestones against established benchmarks or performance of other companies who have undertaken similar projects then permits some robustness to be applied to the development plan.

Responses to Uncertainty and Links to Value Management

Considering Uncertainty During the Project Early Phase

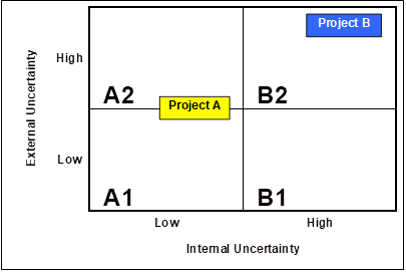

Kolltveit et al place uncertainty in two locations of external and internal occurrence and further distinguish between high and low aspects of these forms of uncertainty. As with a simple risk matrix this enables a particular project to be sited by virtue of its assessed uncertainty profile.

Projects with large external uncertainties (A2 and B2 in figure 1) are described as projects with the potential for large value generation, subject to the management of concomitant risk associated with the uncertainty.

The management of uncertainty during the project early phase is suggested to be a strategic issue and the techniques common to risk management are thought to be useful to aid an assessment of threats and opportunities presented by a high external uncertainty. This is recommended to be carried out by a senior project group gathered for just such an assessment. Noting that an assessment will carry natural biases and be subject to incomplete information, such a project stakeholder group is proposed as the best vehicle to carry out such an analysis.

The representative grouping that a Value Management workshop group ideally is, offers a suitable forum for uncertainty assessment and this is developed hereafter.

The authors promote the idea strongly that it is during the early phase of a project that the best opportunity exists for the generation of value for a project. This is something understood by all value management practitioners where the best opportunity of value enhancement for least cost exists at the earliest stages of a project. Accordingly they advocate exploiting opportunities presented by uncertainty (in its positive benign aspect) during this same project early phase.

The Process within the Strategic Choice Approach

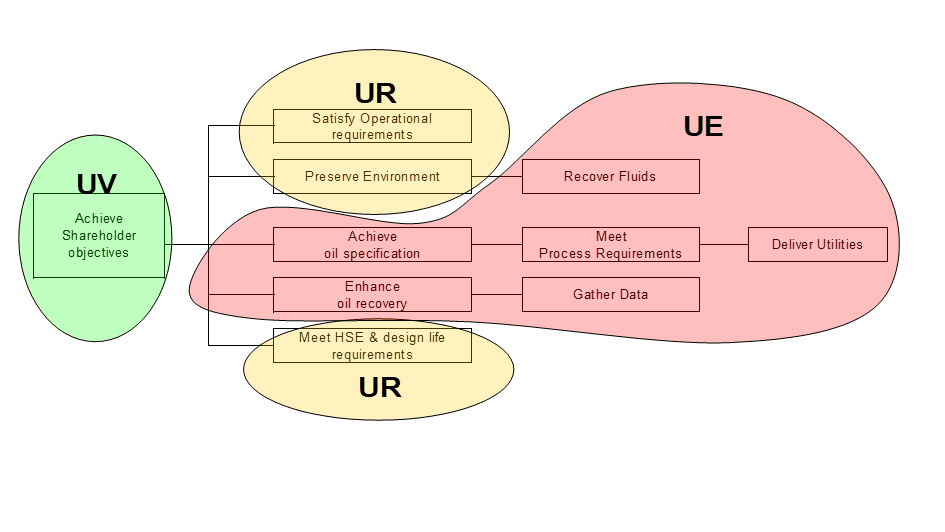

The Strategic Choice Approach has uncovered three fundamental aspects of uncertainty that affect a group of persons attempting to deal with a problem, namely uncertainty about the working environment (UE), uncertainty about guiding values (UV) and uncertainty about related decisions or agendas (UR). Uncertainty is managed within the Strategic Choice Approach by using a workshop which draws on the knowledge and experience of the team addressing the decision problem and like Value Management uses interlinked stages to move the team through a series of self learning experiences. Although the structure of the Strategic Choice Workshop is flexible to enable repetitions of previous stages, it involves passing through four linked phases:

- Shaping – the boundaries of the decision problem are probed by reviewing issues and open discussion to record items that appear relevant to the problem and separately other items that are identified as uncertainties or criteria that later could be used to make comparisons between different options;

- Designing – this phase allows the group to consider responses to the decision problem and whether there are sufficient options in view or whether there are design constraints of either a technical or policy nature that might restrict the scope for combining options;

- Comparing – the issues behind the choices between different courses of action and the consequences of action are considered in this phase and it is in this mode that the uncertainties exposed so far can have the most significant impact.

- Choosing – a closing phase that considers the implementation of chosen courses of action and what other actions may be required in order to achieve the desired results. The time horizon for all proposed actions are also agreed.

The use of such interlinked stages are familiar to a Value Management practitioner by virtue of the use of a work plan that is used to connect different elements of data acquisition, analysis, creativity, evaluation and implementation in a Value Management workshop. However in a Strategic Choice workshop more latitude is allowed for the facilitator and group to move on to further stages before returning again perhaps several times to previous phases, albeit with a modified viewpoint from the accumulated learning experience of elapsed workshop time.

Strategic Choice Approach challenges the normalised ways of working with problems by using a cyclical approach that avoids a linear path to problem solving, acknowledges and uses subjective views of the group, embraces uncertainty and is unafraid to be selective.

The set up and organisation has many parallels with Value Management workshops in adopting an open fraternal approach, tools which are simple and typically graphical but support open exchanges and encourage learning.

The acknowledgement and working with uncertainty in its diagnosed forms recognises the reality of real life situations which coupled with its developed tools and participative approach allows a group to face, learn and develop a course of action that does not simplify problems by ignoring uncertainty.

Bringing Rigour to an Uncertain Future

Courtney and Lovallo’s approach to managing a truly unpredictable and uncertain future for a particular option involves the application of the question ‘what would I have to believe?’ in order for this option to deliver on an otherwise optimistic assessment of possible or promised benefits. The approach for a project that has an attribute of level 4 uncertainty is twofold:

- To require of those charged with the decision of developing further an option to answer ‘what would I have to believe’ and through this to highlight assumptions (often generously over-optimistic) and then key indicators which might act as signposts for the projects development. This is undertaken by members of the project team’

- To investigate further the assumptions and key indicators by bench-marking them against analogous developments, or part developments so as to test the investment assumptions against the actual outcomes for the comparison cases.

These issues perhaps deserve more attention within Value Management workshops where negative criticisms of Value Management results tend to be founded upon the issue of ‘did the workshop really deliver the projected benefits?’ Often there are acknowledged time constraints on workshop time. Under the theme of uncertainty, it is suggested that the failure to fully realise the increase in value of options developed within a Value Management workshop can often be lain at the door of the negative aspect of uncertainty eroding an increase in function, decrease in cost or other value component.

Proposals for the Management of Uncertainty in a Workshop

Pervasive Uncertainty

Uncertainty affects all undertakings concerned with the future and more particularly those with an interest in some way of planning for and predicting the future, as occurs with all major projects. Those projects that hope for the best just have luck and that hope to see them through an uncertain future. Those projects which seek to manage risk at least have a plan of mitigating the negative aspects of a more probabilistic uncertainty, but may miss the chances that come from the early project stage opportunities presented by uncertainty. Such opportunities are fantastic springboards for creativity and it is known that Value Management distinguishes itself by the deliberate use of creativity as one element within its work plan. Creative sessions always appear to need new ideas and boosting and this is perhaps a reason in itself to consider a new idea such as uncertainty.

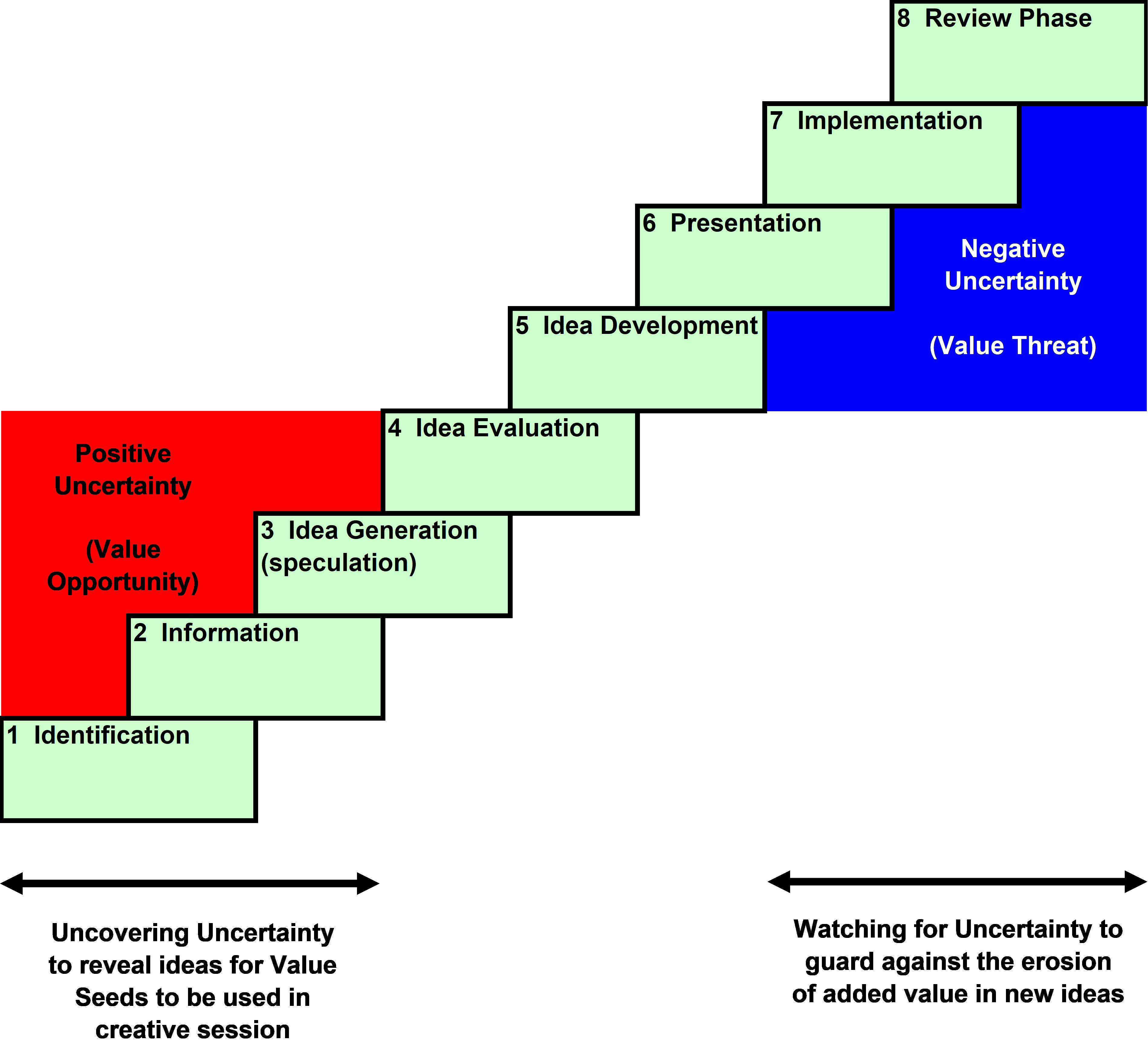

It is suggested that whilst in the early phase of a Value Management workshop the uncovering of uncertainty allows risk and positive uncertainty opportunity areas to be brought into view, later on in the workshop the negative aspect of uncertainty may enter again, but this time to erode the potential of some of the best value adding ideas evolved by the group. This changing face of uncertainty is illustrated in Figure 2.

The challenge then is to utilise uncertainty within a value management workshop during the first stages of the work plan and thereafter protect and guard against the erosion of value contained within ideas developed by the workshop team.

How Uncertain is this Project?

A large and complex project forming the subject of a workshop usually undergoes a value management workshop format that does not change markedly from one project to the next, even if the uncertainty changes. Any change in uncertainty may be only picked up by non-direct means as there is no deliberate mechanism in place to ascertain with the workshop team what degree of uncertainty a project has. An early and deliberate awareness of project uncertainty could be very useful in order to:

- Make the team collectively aware that this project has issues which make it, for example, more uncertain than a similar scope project faced once before;

- Being aware of a projects higher uncertainty and conjoined with its early phase, a team can be obliged by the facilitator to tease out through discussion and questioning those areas of the project that are the sources of uncertainty. It is suggested that these areas can be the seeds of positive value opportunity and deliberately targeted by the facilitator so as to encourage value adding ideas springing from the uncertainties during the creative phase. This is in addition and supplementary to all other ideas that may come up during thethe creative phase.

The simplest mechanism to consider the uncertainty within the project would be to adopt as part of the information and identification initial phase of the Value Management workshop a review of where the project is assessed as being placed on the Project Uncertainty Profile as developed by Kolltveit et al (see Figure 3). An awareness of where the project sits with respect to internal and external uncertainty should provoke a team to consider ways of improving project value by developing ideas to lessen the uncertainty internally, externally or both. The team will also have the chance to think creatively how a project with higher uncertainty could through a focus on the sources of that uncertainty yield new creative ideas on value enhancement than compared to a project with a lower uncertainty profile.

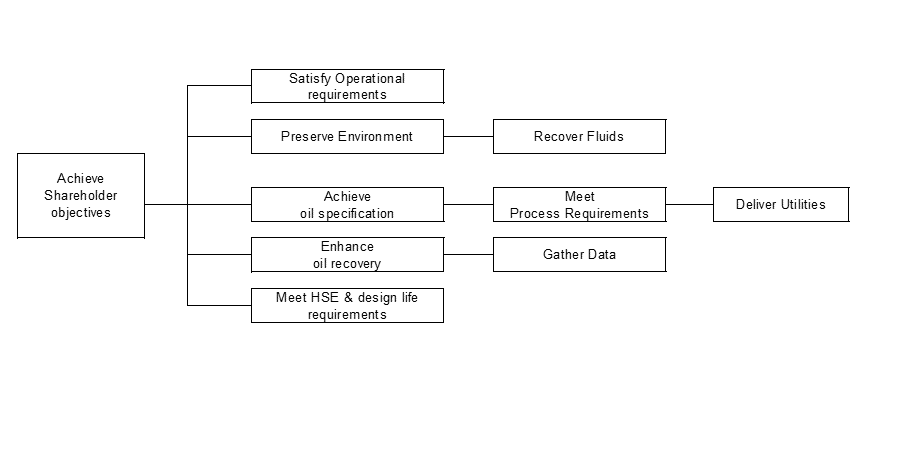

Uncertainty Affecting Functions

Functional analysis remains one of the foremost distinguishing features of the Value Management approach, differentiating it from many other approaches with similar aims and aspirations. Functional Analysis System Technique (FAST) diagramming is, however, not an exact science and there is subjectivity in the diagrams that can be produced by two teams considering the same project. Its main use is to aid and assist a functional based understanding of a project and to investigate how the budget is being spent to deliver the assessed functions. However, an uncertain project subjected to FAST will also have functions with innate uncertainties. If one is aware of this fact, then it may provoke the team to question more concerning the functions and reveal deeper issues associated with the projects functional delivery.

It is suggested that the knowledge of uncertainty provided by the insights of the Strategic Choice Approach can assist a Value Management team to review further the results of functional analysis and by so doing reveal additional issues that may assist the uncovering of ways of adding value to a project. In figure 4a and 4b a simple function hierarchy diagram from a real life workshop is analysed further to ascribe the three forms of Strategic Choice uncertainties to the function families. This simple step can lead to the team considering whether they need to respond to any shared perceptions of uncertainty by looking more deeply into the project environment (UE), guiding values (UV) or related agenda items (UR) affecting the project and the functions. This new step will assist a deeper analysis and from this give the possibility to improve the value added is to the project.

Managing Uncertainty to Protect Against Loss of Value

As a value management workshop proceeds through its work plan stages and the best ideas are distilled and evaluated, typically 10-15 options for value improvement to the project will be gathered. The actual accrual of the envisaged benefits depends entirely upon the satisfactory implementation of the ideas. Often some good ideas with promise may fail to deliver partly on account of their novelty and through this the introduction of uncertainties unforeseen when the idea was developed within the workshop. Reasons for this can include:

- The natural time limits on workshops militate against the thorough consideration of all aspects, particularly negative ones, of a promising idea and time usually becomes more constrained the later into the workshop the team progresses. The development of ideas occurs as one of the later stages within a workshop;

- Sometimes a promising idea will be so novel that the full implications of its adoption are difficult to assess especially within a truncated workshop duration;

- A new idea within a large project can have many unforeseen consequences outside of the immediate environment of the project, as assessed by the workshop team;

- There exists little formal guidance for workshop teams on how to think through the implementation of ideas and consider as fully as possible how uncertainty can be best avoided so as to gain the full benefits of the new idea.

In such circumstances the question of ‘what would I have to believe?’ in order for a good idea to fully deliver its potential is proposed as a useful tool to help a team think through the stages and signs for an idea to realise its full potential. Such a simple question is easy to grasp and should not add any noticeable time to the development stage of ideas within a value management workshop.

Conclusion

Uncertainty is present within any contemplated activity or undertaking. Although by its very nature uncertainty presents a difficult subject to precisely tie down, there are strategies and knowledge that can be applied within a Value Management workshop which can deliver additional value. An initial investigation should be conducted by the team to consider just how uncertain they think the project is that they are reviewing. During the initial stage of an uncertain project the identification of sources of uncertainty flags up to an alert team and facilitator the possibility of areas where value may lie hidden. These areas can be dug out by deliberate questioning concerning the nature and location of uncertainty within the project overall and later within individual functions. In the latter case the attribution of uncertainty components as developed within the methodology of Strategic Choice Approach can lead a team to consider whether they need to enquire further concerning a project’s guiding values (UV), project environment (UE) or the wider related agenda issues (UR) surrounding the project. Such an enquiry may allow a team to catch additional issues that permit a richer yield of value adding ideas.

The delivery of value as promised by the best ideas coming out of a workshop can be reduced by new uncertainties injected by the selfsame good ideas. Again by being alert but this time to the atrophying aspect of uncertainty and examining what is required to be believed by the team for the option to be successful, a useful degree of pragmatism can be introduced that balances against a teams optimism bias.

Overall, uncertainty is too important a subject to ignore within a Value Management workshop as it has a strong links to the uncovering of creative value ideas and to the dissolution of value potential. This paper proposes the adoption of approaches and knowledge already offered by others to the Value Management community in order to deliver an increase of value for projects subjected to workshops.

References

- Achrol, R.S.

‘Measuring Uncertainty in organisation analysis’

Society Scientific Research, 17(1), 66-91.

- Courtney, H & Lovallo, D

‘Bringing Rigor and Reality to Early Stage R&D Decisions’

Research • Technology Management, September- October 2004

- Friend, J & Hickling, A

‘Planning Under Pressure – The Strategic Choice Approach’

Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 3rd Ed. 2005 ISBN 0-7506-63731

- Galbraith, J.R.

‘Organisation Design’

Addison Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1977

- Kolltveit B.J., Karlsen, J.T., Gronhaug, K.

‘Exploiting Opportunities in Uncertainty During the Early Project Phase’

Journal of Management in Engineering, ASCE October 2004

- Rosenhead, J., Mingers J.

‘Rational Analysis for a Problematic World Revisited’

John Wiley & Sons, 2001, ISBN 0-471-49523-9

Association of Project Management www.apm.org.uk

Project Management Institute www.pmi.org

Insights & News

International Women in Engineering Day: Meet April, Najma and Nora

In this second edition, meet April, As-Build Coordinator & Lead CAD Associate at C&I Engineering, a company acquired by Penspen in 2024; Najma, Senior Finance Officer based in Abu Dhabi; and Nora,...

International Women in Engineering Day: Meet Shobhina, Maria and Rachael

The energy industry is changing rapidly, and meeting the challenges posed by this transition requires a diversity of talent and perspectives – something that we’re committed to addressing in a...

Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage – What are the Real Challenges & Costs?

As the global push for net zero intensifies, Carbon Capture, Utilisation, and Storage (CCUS) is emerging as a critical technology to decarbonise energy supplies and industrial processes. With the...

Challenges and Considerations for Hydrogen Integration in Natural Gas Pipeline Networks: A Comparative Screening Methodology

The global transition to hydrogen is accelerating, and repurposing existing natural gas pipelines is a critical step towards a low-carbon future. However, ensuring the feasibility, safety, and...

Penspen and Cosasco Announce Strategic Collaboration to Advance Corrosion Monitoring and Management Solutions

(L-R Brandon Alexander – Penspen US Director, Peter O’Sullivan – Penspen CEO, Philip Bourop – Cosasco President, Om Mourya – Cosasco VP of Sales, Gustavo Romero...

Penspen Training Courses Achieve IGEM Recognition

Penspen’s asset management training courses were recently recognised by IGEM, the Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers. This prestigious recognition demonstrates that Penspen’s...

Penspen Strengthens North-East Commitment with New Aberdeen Office as Growth Accelerates

New Office Investment Boosts 200-Strong Team’s Capacity to Deliver Key Energy Transition Projects (Darren Bartlett, Penspen’s Director of EPM and Energy Transition and Grant Lunn, CEO of...